Sang Hyun Koh:

Indecipherable Art

Interviewed by Eun Hyung Chung

Sang Hyun Koh is an artist who creates works based on self-satisfying algorithms. Seeing his work requires a process of decoding. His works have a strict logic or order which is difficult for viewers to read. Ironically, this moment of friction prompts our curiosity and makes us take a closer look into his works. Deeply interested in the natural sciences, particularly zoology, Koh tries to maximize his logical inconsistency when connecting science to his worldview.

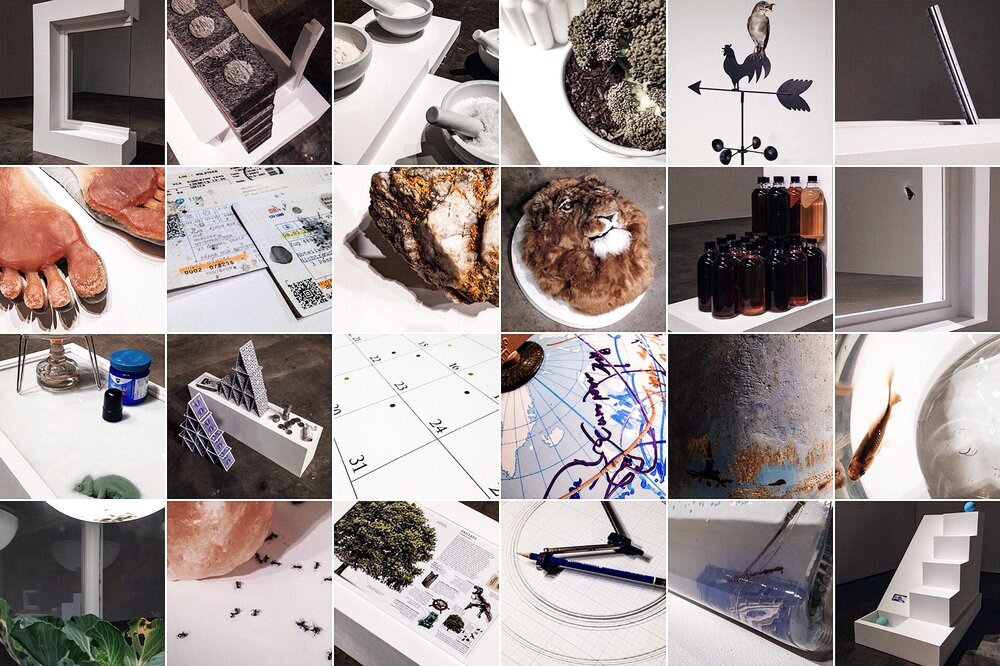

Sang Hyun Koh, The Pole and The Opposite Always Coexist, variable installation, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

Eun Hyung Chung: The first words that came to my mind when I saw your work were “perfectionist” and “professional.” In other words, you have a great talent in making. Have you been dedicated to sculpture since childhood? Could you tell me a little bit about your background?

Sang Hyun Koh: It has been 16 years since I lodged myself in sculptural practice. Even if the multidisciplinary value dominates the global atmosphere, and a change of mood to the diversity of specifications has even occurred in Korea, the somewhat conservative attitude of keeping my position in the same sculptural field has permeated my entire career. As one of the Third World countries having the belated inflow of postmodernism from the late 80’s to the early 2000’s, Korean educational policy encouraged youngsters to specialize in a specific single major, and I spent my teenage leaning on this educational environment. Plus, as a transitional or “squeezed” generation between the so-called old boys and young kids of the Korean art world of the 2000’s, I have been forced to pursue very strict academic apprenticeships and traditionally technical fabrication practices as I scaffold my own identity.

EHC: Your answer reminds me of “The 10,000 Hours Rule”, the rule that at least 10,000 hours of training is required to become an expert in one field, which I heard about several times in my childhood. Is your practice now similar to what you liked doing as a child? Where did it all begin?

SHK: Marcel Duchamp was deeply interested in impressionism and Picasso was dedicated to eclecticism. Everything has changed except the very instinctive human desire to express. In my undergrad, my art practice started to dive into the allegorical impulse and constructional installation, which was merely a result of studying art history.

EHC: Then, after you studied art history, how did your thoughts change? I wonder how you would define contemporary art.

SHK: As the term “contemporary" is relative, there’s no significance for me in the idea of contemporaneity. I’d rather trust dualism or dichotomy. In relation to dualism, the “Paragone” debate, which was the main flow of Western art history of Comparison, especially in Renaissance, has been a penetrating issue in human cultural history and forever. In a broad range, since the Neo-Dadaism took the mound, so far, it’s been an era of romantic aspect including postmodernism, feminism, perspectivism, localism, nationalism, etc. Trusting F.P. Chambers’ logics[1], I’m classical. I predict that the next generation of contemporary art should be the classical aspect or era of universalism again and this explosive time of particles should be tossed and changed by a certain universal rule, and irresponsibly no one knows yet what the standard of the flow is.

Sang Hyun Koh, Zeno’s Paradox, variable installation, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist. (left)

Sang Hyun Koh, A Single Locomotion (Twenty-three Chameleon’s Feet Reaching the Ultimate Finality of Uselessness), , 2015. Image courtesy of the artist. (right)

EHC: I understand your prediction of the next generation of contemporary art because new eras of art always appear to emerge against the previous era. From now on, I would like to move on to our next topic: your artistic practice. In terms of materials, do you have any materials that you prefer? How do you choose materials?

SHK: For last decade, I have usually produced large installations with wood, because I have been obsessed with static precision. But basically, there’s no boundary in the choices of materials to answer the artistic oracles. For each project, the appropriate ratio, dimensions, and textures of elements are needed to be precise to the original and ideal image or system in the artist’s brain. Even if the images hovering an inch above my head are just delusional. If there’s a satisfactory algorithm traceable from myself, the projects or the pieces should sincerely follow the original image, and the material selection is the means for that. However, I’m not familiar with performance, video or photography yet.

EHC: Since you used the term “satisfactory algorithm”, it seems like you have a very strict and firm standard or rule when making works. Is there a specific feeling that you try to achieve?

SHK: There’s no artist without the feeling or will to make achievement in working. I require self-confidence from my work. This confidence springs up out of the artist’s sense of responsibility towards their work. The more dedicated artists are to the process of work, the more responsible the spirit is. The dedication is quite clear. It could be the proportion to time consumptions, the production of visual spectacles, the fullness of interpretive possibilities, or splendid background texts and contexts, but all these are trash and fraud – I warn this era of interpretation and context. The only commitment is to keep my contract with myself. I need to acquire or create a system for each piece from myself. There are two ways to reach the ultimate line of humanity. One is the pursuit of intersubjective objectivity as “Round Table” which I call “Average Value”. This way needs a public and can be formed only in communities. Even if art can be a communicative practice, I would rather believe that art, together with science and literature, should be the pursuit of “Absolute Value” with a single person by and for oneself. Without this severe exclusion from the society, no artist can be born. Ironically, I’m including myself in this institution and I keep placing myself somewhere for a sense of belonging but at the same time, I should radically try to exclude myself as dumb and blind from societies. I should follow my own judgement. This is the number one principle of the attitude I want to achieve in my practice as long as I’m doing art.

EHC: Sometimes, it might be a lonely battle for you to isolate yourself from the society that you seem to inevitably belong to. Then, when do you feel satisfied with your work? In other words, what are the criteria for success in your artworks? Or does that matter? Tell us about what the larger context for your artistic creation is.

SHK: The only complete achievement is to strictly follow the original idea of work. I have a habit setting all of the mappings of my ideas before fabrication. If there’s a loose connection between images and lessons, the ideas should be buried by myself. Three conditions ought to be accomplished for me to deem a piece of mine successful: self-satisfaction of the image, inclusion of human lessons as educational materials, and inscrutability or inaccessibility. The last two conditions collide, and I enjoy this antinomy.

Sang Hyun Koh, Dung Beetle Rolling the Earth, , 2017. Close-up Image. Image courtesy of the artist. (left)

Sang Hyun Koh, This Case Is in The Process of Installation, , 2018. Image courtesy of the artist. (right)

EHC: Your particular interests in contradiction and inconsistency make me wonder about your influences. Who has been your biggest influences over time?

SHK: Marcel Duchamp taught me the importance of duality rather than the usage of ready-mades or the importance of choice, which he is more commonly associated with. René Magritte taught me about the comfort of discomfort rather than semiotics. Hieronymus Bosch taught me the human instinct to be obsessed with totality and enigmas rather than the possibility of multiple interpretations. They all taught me inscrutability as a critical artistic mode.

EHC: On the contrary, are there any artists who have influenced you, but that you don’t necessarily like?

SHK: They should be the colleagues in my college, if I may privilege them with the title of artist. Without any hostility and with a kind of suffocation from contradictions, we have constantly practiced criticism and critique for our art as the institutional objectives. The main issue has been the inscrutability of my work, where meaning is injected into objects with little explanations and disconcerting titles. On the other hand, most of my other colleagues, the peacemakers, tend to somewhat unconditionally absorb the feedback about their own work in positive ways. I noticed that practically everyone tries to read the artwork – using logos to understand imago, and in order to evade misinterpretation, they wonder badly about the original idea of the artist. Although people mostly think that originality has been disrupted in the field of art, ironically the original idea of the artist is still the main reference for their own interpretations. Anyway, in this context, I have tried to produce work that is as difficult to read as possible. I consider this to be the first time that I have really looked at myself.

EHC: I heard that you’ve experienced various educational environments. What inquiries did you deal with through your work before you came to RISD? And compared to the previous works, what stayed consistent and what changed?

SHK: There has been no change since RISD. My inquiries are allegorical games with scientific facts which are relative through time. With my interest in natural science, mainly zoology, I naturally drive scientific materials into my work which touch on how I look at the world as well as connecting my interests and my practice. Using scientific materials surrounding this planet and our human community, I want to reveal humanity by concealing meaning under the physicality and image of my work. This kind of ethology has been driving force for me to create my art for a decade and this is just the beginning for me.

Sang Hyun Koh, Life of Someone Who found the Gold Underneath His Bed, , 2016. Close-up Image. Image courtesy of the artist.

EHC: What are the proper ways to see your work? Is there any device that can help viewers understand your work a bit better? I am curious if you have a certain point of agreement between your work and the viewers in mind. Tell us about your story of a particular space and experience there.

SHK: As I mentioned, my projects usually start from scientific study or the regurgitation of my scientific knowledge. It is filtered in order to present clues towards hidden, meanings. The standard that I use to transform the fact into allegory should be determined purely by myself. To connect the facts or normal science with value is the logical inconsistency and I want to maximize this fallacy. Thus, my way to see the work is only to check whether my Sollen-當爲(shouldness) in each piece is properly matching or not through my logics – there’s no common point of compromise with viewers, which causes cacophonies about accessibility.

EHC: Now, I would like to change our subject to your environment, RISD. How does it feel to be in RISD or in Providence? Are there any aspects of life in Providence which are different from home?

SHK: I’m quite satisfied to be here. In order to throw a nutritious comment for RISD, especially for the Sculpture department, I believe the only problem of RISD is the critiques. After all, they go too positive. Surely, the climate of not invading the identities of others could be the neutral virtue and the human pursuit of intersubjective objectivity is the reason for the existence of critique. However, in the critique, the ‘Average Value’ is not that important. In the situation where artists are present with their work in the same space with others, the good critique, I trust, tries to harshly break down the artist’s identity, due to the fact that critique does not take place in the field of emotion. It is axiomatic that the only necessity is the ‘Absolute Value’ of the artist – if the intervention of the views of audiences is required at all to construct and encourage the identity of the work, I trust that the responsibility for the artwork is divided proportionately like so: one third for the artist, the piece of art and the audiences each. In addition, the audiences’ portion of 33.3% should be divided by the current global population (about 0.000000000129702% for each viewer at this moment). Even if the breakdown of identity or intention occurs in the critique, the stabbed identity is not broken, but rather becomes even more solid. This is the only methodology to acquire real artists in our human community, and the only mission of an effective institution.

EHC: I am glad that you are satisfied with your life in Providence. I also understand your thoughts about critiques because critiques in our home country, Korea was much harsher and more direct. Since graduate students are not always mature artists, I do think that although telling the truth can be hurtful for them. Outside of critiques, is there a mentor at RISD who has been influential?

SHK: I can proudly tell that one single effective peer can be the absolute artistic driving force to place oneself as an artist, regardless of the full package of facilities and faculty members. I struggled for a while at first to find the right person who does not support or advocate for me but with whom I can communicate about art and work without superficial rhetoric. Fortunately, I found one in another department in this school and I hope he can be consistently a great asset for my lifetime.

Sang Hyun Koh, Faeces, variable sizes and variable installation, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sang Hyun Koh, Faeces (detail), variable sizes and variable installation, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

EHC: I can’t believe that we have already finished our first year. As you segue into the final year of the MFA program, what do you expect for the second year? Do you have some goals? And do you have anything you want to do after graduation?

SHK: I’ll keep warning myself away from losing my creed. I wish to produce mappings which will keep me fully satisfied for the next decade and which shall be the foundational rock for my future work after this institution. Belonging to institutions doesn’t necessarily mean that students are required to replenish their system, but this is a good stimulant to drive myself to observe the given schedule to achieve something within a limited time span. I have felt a certain thirst for satisfaction for the last two years after the installation project ‘Faeces’, feeling that my recent practices lacked a cognitive tessellation between consequential images and innate ideas.

[1] Frank P. Chambers is the author of "The History of Taste; An Account of the Revolutions of Art Criticism and Theory in Europe" and "The Cycles of Taste; An Unacknowleged Problem in Ancient Art and Criticism". He drew "Classical Aspect" and "Romatic Aspect" into chapters to address and compare tastes in art history.